Movement Stories: A. Schild 1173 Bumper Automatic

Bumper automatics, an early take on self-winding mechanisms that uses a semi-circular “bumper” weight which swings back and forth—literally bumping against springs or buffers—to wind the mainspring without a full 360° rotor, are reasonably common in the mid-century watch world. I personally have several bumper automatics in my private collection, including examples from Omega, Jaeger LeCoultre, and Univeral Genève. While these are all in-house movements, they all follow a very similar design. The A. Schild 1173, on the other hand, is a bit different: it’s a very early, mass-produced automatic first introduced in the mid-1930s, and its bumper-style architecture traces a direct lineage back to the original John Harwood automatic concept. Let’s take a close look as this design as it comes back together on my restoration bench following a cleaning.

The base movement, has a pretty standard 15-jewel layout, with an extended 3rd wheel pivot to mount the intermediate wheel for the indirect center second hand drive. However, careful observers will note that there’s something interesting going on with the winding mechanism. First, the crown and ratchet wheels are deeply recessed into a particularly thick barrel bridge. You can also see spring mechanism mounted around an unjeweled pivot nestled between the two wheels (more on that in a moment), and another pivot point underneath a small hole in the crown wheel cover. Most oddly, however, there’s no click! You’re not imagining it: unlike pretty much every other automatic movement I have worked on, the AS 1173 eschews a conventional click mechanism that operates independently from the automatic works.

Unfortunately, this means there’s also no way to power & test the watch without installing more of the automatic parts. First things first, however - let’s install the indirect center second drive & pinion:

Nothing fancy here. The intermediate wheel is press fit onto the extended 3rd wheel pivot, and the center seconds pinion is held down with a simple spring, which serves to both hold the pinion in place and to induce a tiny amount of drag to prevent gear lash a keep the second hand from stuttering.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the automatic mechanism…

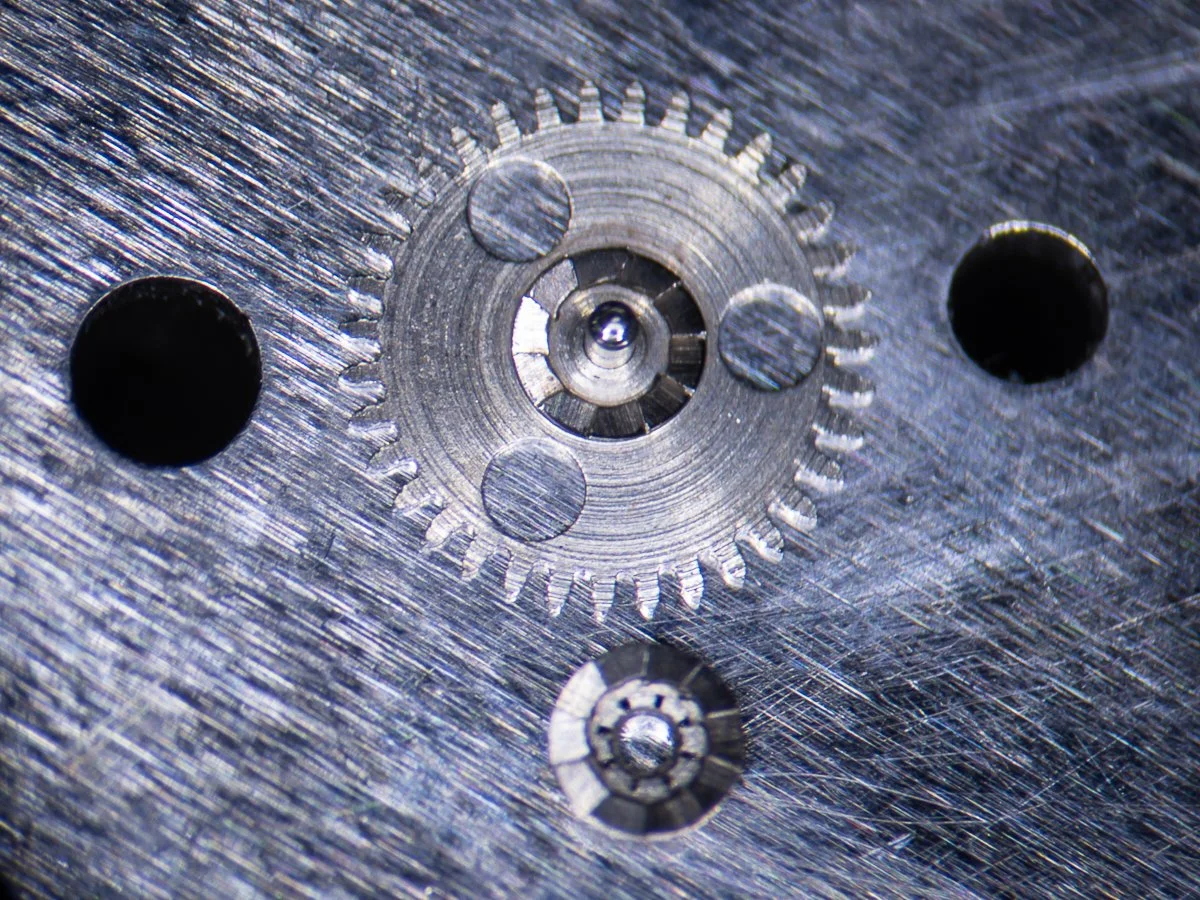

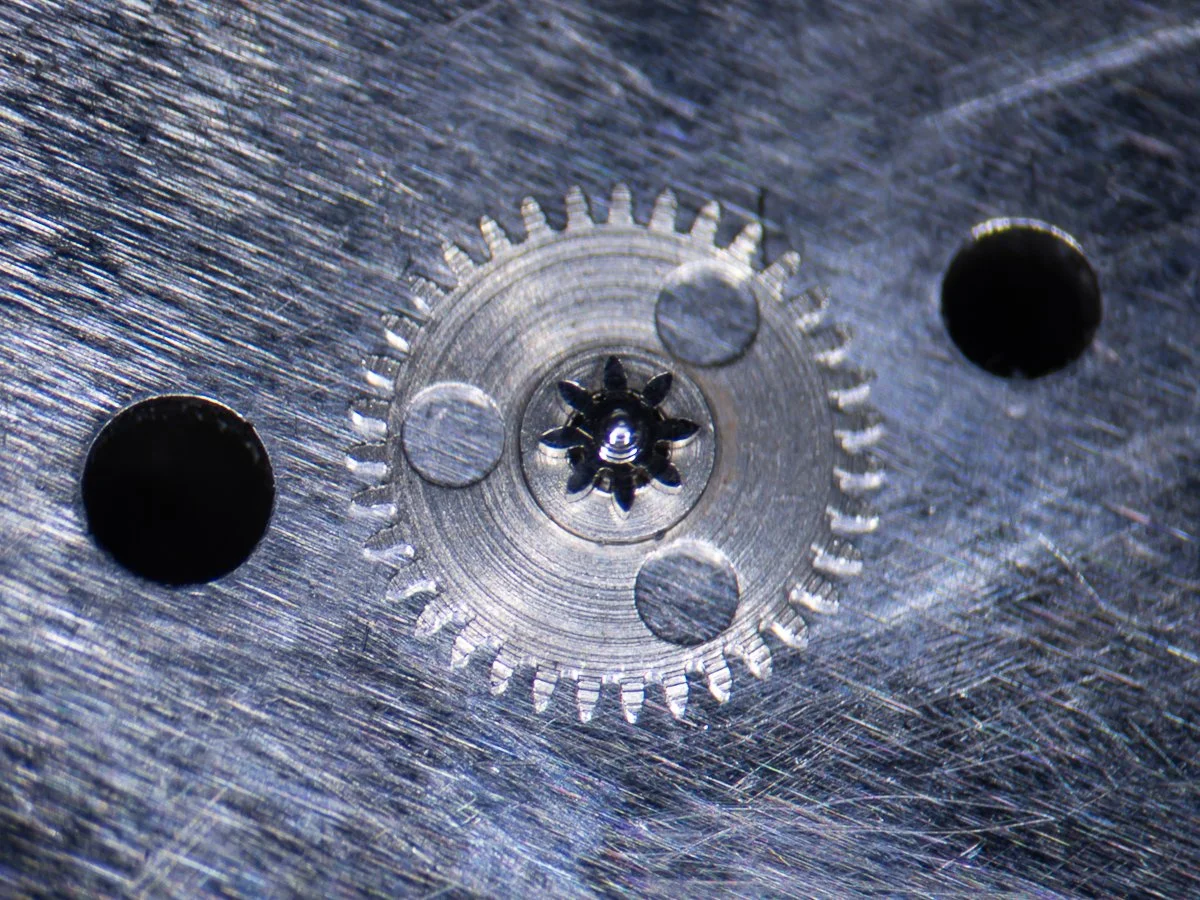

The two open pivot points called out above support a pair of intermediate driving wheels for the automatic mechanism. This stack of wheels is quite tall - which explains the height of the barrel bridge. Later automatic movements started to prioritize thinness, but it clearly wasn’t a big concern in this early design. The wheel with the three holes includes a Breguet-style ratcheting mechanism, which utilizes the spring which was visible in the previous photos. Here’s are a few closeup photos of the underside of this mechanism. The first shows the separate ratcheting components. The second shows the lower ratchet piece installed, with the pinion teeth that engage with the ratchet wheel:

This ratchet mechanism serves to decouple the automatic mechanism for manual winding. It’s pretty effective in this respect - the manual winding feel of this movement is pretty much indistinguishable from a conventional manual wind watch, which was a priority for designers in this era. That said, there’s still no click, but we’re finally getting to that:

Finally, the mystery of the missing click is solved. It actually engages with the upper intermediate wheel of the automatic mechanism. Note the loooong integrated click spring which crosses entirely over the lower intermediate wheel and engages with a post in the top of the barrel bridge. Many automatic movements have some sort of secondary click mechanism integrated into the automatic works to capture small inputs from the oscillating weight, but this is the only automatic I have worked on where this works as the primary click mechanism for the movement.

The upper pivots on these intermediate wheels, as well as the click, are located in a thin plate that screws onto the top of the barrel bridge. The upper pivots for the intermediate wheels are both jeweled, which, not coincidentally, brings the jewel count for the movement up to a highly-marketable 17. There’s a small hole in the plate that provides access to the click so that the power can be let down. By the way, if you’re thinking that getting all of these really tall, top heavy components to seat in these pivots was probably a very fiddly operation, you absolutely correct. This is particuarly true becasue the lower intermediate wheel doesn’t want to sit upright due to the ratchet/spring mechanism underneath. If you ever work on one of these yourself I recommend snagging the top pivot of the lower intermediate wheel in its pivot before moving the plate laterally into position.

At this point, the watch will finally take a wind, so it’s time to install the keyless works and the rest of the escapement and make sure everything is running correctly

Flipping things over, the dial side of the movement, and the keyless and motion works are all convention Swiss design, so not much to say here…

All lubricated, regulated and running like a champ!

Now it’s time to finish off the automatic mechanism. As you’ll see, it still has a few surprises in store!

The oscillating weight is sandwiched betwen two plates, which attach to the top of the train wheel bridge with a pair of screws. A wheel surrounds the oscillating weight pivot, and engages with the upper intermediate wheel that we installed previously. This wheel is free-spinning however, so there’s one more piece to add before the weight can actually wind the watch…

… and it’s another click-type mechanism, which sits on a post that is actually on the oscillating weight itself. It has an integrated spring that engages with a second post. With this click mechanism in place, the, central rotor can only rotate freely in one direction, so it will wind the watch when the rotor turns counter-clockwise. This secondary click is retained by a simple screw-down top plate.

As an aside, the pins that support this click mechanism are not machined into the oscillating weight - they are separate steel pins that are press fit into holes in the plate. The bad news about this is that they can fall out, which had actually happended to this movement. The good news is that they can be replaced, and I was able to source another pin from a partial donor movement. It’s easy remove and install these pins with a basic staking set.

And voila, the fully assembled winding mechanism in action! Definitely not the most efficient design, especially compared to later evolutions of the automatic watch, but it’s still pretty clever.

If you’re wondering about this particular movement’s ultimate home, it resides in a lovely early 1940s Cortébert that now resides in my private collection: